Pre-processing

| |

| Lecture video: |

web TODO Youtube |

|---|---|

Data pre-processing and normalization

Drop any distinctions that are not important for the output.

Inspecting Text Data

Text Encoding

Two texts that look the same might not be identical. MT systems do not see the strings as humans do but instead, they work with the actual byte representation. Therefore, data pre-processing is a very important step in system development.

Unicode includes a number of special characters which can complicate text processing for an MT system developer. The following table contains examples of some of the more devious characters:

| Code | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| U+200B | Zero-width space | An invisible space. |

| U+200E | Left-to-right mark | An invisible character used in texts with mixed scripts (e.g. Latin and Arabic) to indicate reading direction. |

| U+2028 | Line separator | A Unicode newline which is often not interpreted by text editors (and can be invisible). |

| U+2029 | Paragraph separator | Separates paragraphs, implies a new line (also often ignored). |

Decode Unicode is a useful webpage with information on Unicode characters.

Script/Characters

Unicode often provides many ways how to write a single character. For example "a" might be written with Latin or Cyrillic script.

VIM tips

Set file encoding to UTF-8:

:set encoding=utf8

Show the code of character under cursor:

ga

Set BOM (byte-order mark) for current file:

:set bomb

Hexdump: xxd

==

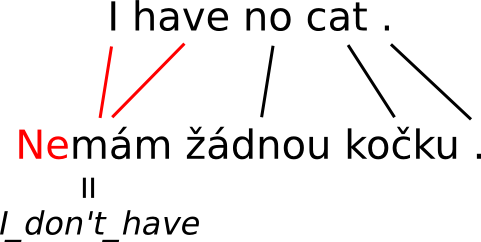

Negation in English-Czech Translation

In some cases, the statistical approach leads to systematic errors. The picture illustrates a common issue with negation -- in many languages (such as Czech), negation is expressed by a prefix ("ne" in this case). Moreover, Czech uses double negatives -- the sentence:

- Nemám žádnou kočku.

Its English translation is:

- I have no cat.

Although word by word, the Czech sentence actually says:

- I_do_not_have no cat.

Most statistical MT systems are based on word alignment, i.e. finding which words correspond to each other. From this sentence pair, the automatic procedure learns a wrong translation rule:

- I have=nemám

Whenever this rule is applied, the meaning of the translation is completely reversed.

Named Entities

Other examples of notorious errors include named entities, such as:

- Jan Novák potkal Karla Poláka. -> John Smith met Charles Pole.

The name Novák is sometimes translated as Smith as both are examples of very common surnames in the respective language.

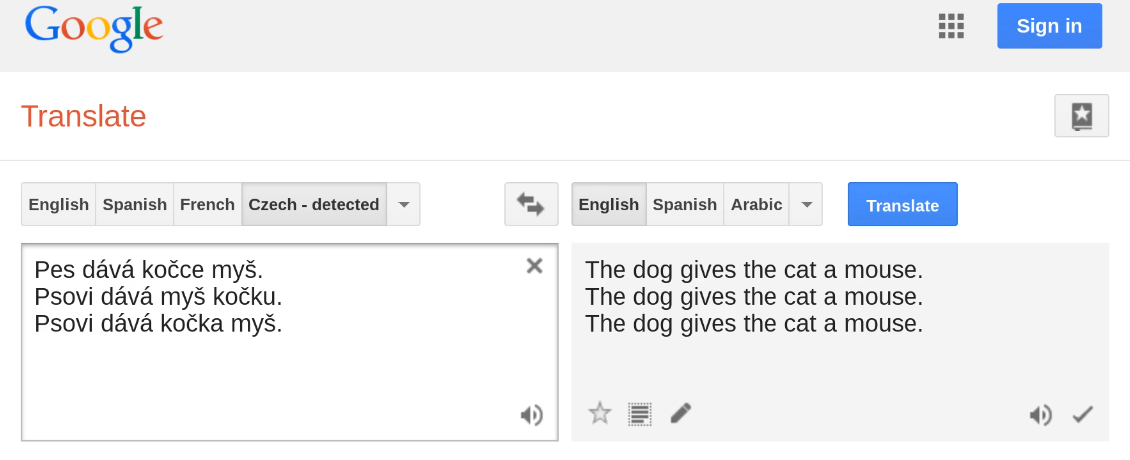

Inadequate Modeling of Semantic Roles

There is also a disconnect when translating between a morphologically poor and a morphologically rich language. While the first tend to express argument roles using word order (think English), the latter often use inflectional affixes. A statistical system which simply learn correspondences between words and short phrases then fails to capture the difference in meaning:

- Pes dává kočce myš. (the dog gives the cat a mouse)

- Psovi dává myš kočku. (to the dog, the mouse gives a cat)

- Psovi dává kočka myš. (to the dog, the cat gives a mouse)

All of these examples are translated identically by Google Translate at the moment, even though their meanings are clearly radically different.

Numerals

Translation dictionaries of statistical MT systems are full of potential errors in numbers. Consider the possible translations of the number 1.96 according to our English-Czech translation system:

1.96 ||| , 96 1 , 1.96 ||| , 96 1 1.96 ||| , 96 1.96 ||| 1,96 1.96 ||| 1.96 1.96 ||| 96 1 , 1.96 ||| 96 1 1.96 ||| 96

While the wrong translations may be improbable according to the model, they can still appear in the final translation in some situations.

Moreover, MT systems will often translate the actual number correctly but confuse the units, e.g.:

- 40 miles -> 40 km

On the other hand, such situations can lead to peculiar translations of numbers observed in parallel data:

40 ||| 24.8548 (km) (miles)